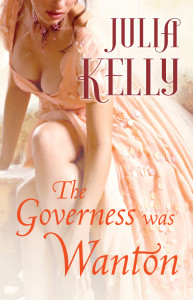

On Thursday, I turned in the developmental edits for my upcoming contemporary sports romance Changing the Play which will be published under a new pen name, Julia Blake. Authors know that this is cause for celebration. Developmental edits are a big deadline, and getting them out of the way is a huge relief. But others might be wondering what that actually means. Even though I'd published independently before signing with Pocket Books, I had to admit to being fuzzy on the whole publishing process at traditional houses. Today I'm going to try to walk you through some of the major steps that gets a book from draft to publication using my experience with the second in my Governess series, The Governess Was Wanton.

The First Draft

The First Draft

It seems logical that the first step in publishing a book is to actually write the book. Depending upon where you are in your career and the terms of your deal, however, there might be a whole negotiation before you ever write a word of prose. (Selling on proposal is a topic for another day.)

When my agent sold the Governess series, we had one completed book (The Governess Was Wicked) and proposals for two others (Wanton and The Governess Was Wild). Those proposals were really just two to three page synopses of what would happen in the book were I to write it.

If you have a completed novel when you strike a deal, the editor can begin working on it immediately. However, you've sold on proposal or there are multiple books in a deal and not all are written, this is the time when an author's got to get to work. When my Governess deal went through, my editor was able to get cracking on The Governess Was Wicked immediately, and that meant I had to get writing Wanton STAT.

I wrote Wanton over about five weeks, revising it up until the deadline. Then, blurry eyed and tired, I turned it in to my editor. That was stage one complete.

Developmental Edits

My editor took my first draft of Wanton and read it through. Then she wrote me an edit letter which is a document with recommendations about what to change, which parts need to be strengthened, and what new directions she'd like to see the story go in. Often these are very big picture changes to a book that develop character and plot (ie developmental edits).

In the case of Wanton, the edit letter included a big ask: rewriting the ending of the book because it was too similar to the ending of Wicked, which would be published immediately before it. Getting a note like that is nerve wracking because it seems like such a huge undertaking. ("I have to rewrite the whole end of a book? How do I even do that?!") In the end, however, my editor was absolutely right, and the new ending has one of my favorite scenes I've ever written.

Accepted Into Production

Once you've handed in your dev. edits and your editor has gone through them, they might ask for another round of edits. However, if they're happy with the changes made, your book will be accepted into production. Rejoice!

This is typically when authors get paid some part of their advance. (Advances are split up into parts. I've heard of a lot of different advance structures. So far I have been paid half on signing and half on acceptance of the manuscript.)

Line and Copy Edits

Next my editor did a line edit of Wanton (think a very close, line-by-line reading of the content of the text with lots of comments and markups in track changes) before she hands the book off to a copy editor. Some editors may send the line edits to their authors for approval and changes first, but the way we work I got the line edits at the same time as the copy edits.

The copy editor is looking for technical, grammatical problems with the manuscript. This is also the stage where the manuscript is checked for consistency. Copy editors have to be very detail oriented, and I've got a huge amount of respect for them because their job seems impossibly hard to me.

When Wanton went for copy edits, the copy editor made a list of all names, places, and dates referenced in the book. This is like a little bible that your book (and your series if you wind up writing multiple books in the same world) has to adhere to. They're looking for consistency in names, timelines, physical descriptions. It turns out I'm not a strong timeline writer (I'm trying to get better!) so ages and dates are challenging for me. I received several notes on Wanton about whether someone was 28 or 30, what color some else's eyes were, etc.

When I got back my line and copy edits, everything was marked up in track changes. This was my time to then accept or reject the changes in the manuscript. If I agreed with my editor and the copy editor, I would accept a change. If I didn't, I would STET the edit in a comment, which basically meant, "I don't agree with you, please leave the text as it was." With historical romances you have to be particularly careful because not everyone is as familiar with conventions of the time like how siblings were addressed. (I'm the eldest of two sisters, so I would've most often been referred to as "Miss Kelly" and my younger sister would've been "Miss Justine" until either or both of us were married.)

This was also the time where I got to write my dedication and my acknowledgements pages.

Proofs

Once you send back your copy edits, it's time for the pages to be set. This is the first time your book looks like an actual book. Since Wanton was published exclusively as an ebook, this meant that my editor sent me a PDF proof of what the book was going to look like on an eReader screen. This is particularly exciting because in my case it meant seeing the title page, pretty chapter headings, page breaks, etc.

The purpose of looking over a proof is to make sure that all of the changes from the copy edits made it in. It's also a time to sweep for typos. Thankfully I was far from the only set of eyes on the book because at this point I'd read my own manuscript at least eight times. Try editing something you've written and read that many times. It's...hard.

Proofs are the only time that I actually print out and hold my book anymore. I mark up actual pages with colorful pen (my favorite is pink which, now that I think of it, may delight or irritate my proofreader) and then send photographs of the galleys back to my editor to point out where I found typos.

Proofs are not the time for major content changes to a book. They are, essentially, a last check of the book to make sure everything looks okay.

Publication

Rejoice again! You have a book that readers can actually read!

There's a lot more that goes into prepping a book for publication including back cover copy and marketing, but that's a whole separate blog post for another day. In terms of the editorial process, you're done and ready to move on to writing your next great novel because writers never stop writing.